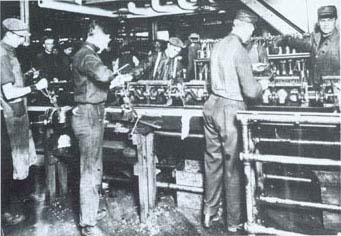

It appears to us that despite the general enthusiasm (at least amongst native English speaking EFL teachers) for pair work , there is very little critical assessment of its widespread use. This is particularly the case with most initial and post certificate teacher training courses in EFL, where ability to demonstrate effective pair work (and subsequent monitoring) is essential to passing the course. At Marxist TEFL, however, whilst not denying the positive effects of various forms of peer orientated activities, we seriously question this “stop-watch” approach to learning and ground current enthusiasm for such activities in Taylorist managerial ideology. In short, we are being asked, as teachers, to replicate within our classrooms the inhuman and alienating work practices of the some of the worst workplaces.

It appears to us that despite the general enthusiasm (at least amongst native English speaking EFL teachers) for pair work , there is very little critical assessment of its widespread use. This is particularly the case with most initial and post certificate teacher training courses in EFL, where ability to demonstrate effective pair work (and subsequent monitoring) is essential to passing the course. At Marxist TEFL, however, whilst not denying the positive effects of various forms of peer orientated activities, we seriously question this “stop-watch” approach to learning and ground current enthusiasm for such activities in Taylorist managerial ideology. In short, we are being asked, as teachers, to replicate within our classrooms the inhuman and alienating work practices of the some of the worst workplaces.

For example, take this piece from materials writer and teacher Liz Regan(1)

- Make a list of pairs of names before the lesson starts or while the students are coming in, or just tell them when the time comes: “Gianni, you work with Paola; Chiara, you’re with Stefano this time.”

- If there is an odd number of students make a group of three but break them up later in the lesson and put them into pairs with someone else so they get more chance to speak.

- You could put them in small groups to start with if the activity allows. You could even make the activity a competition in small teams if the activity allows, seeing which team gets the most answers right. Use the board or a piece of paper for keeping score.

- Change the partners quite often so that the students don’t get bored with their partner. This is especially important if there is a student who isn’t very popular with the others.

Now Liz is clearly a highly intelligent and committed practitioner who, incidentally, has taken the time to share her ideas and experience with us free of charge. This does not change the fact though that, in perfecting the art of this type of pair work, she is in fact perfecting Taylorism (2) within the classroom. A regime designed to break up genuine social relationships , assign fixed non-negotiable tasks and then monitor its subjects in their performance of the same. Indeed, if we look at Liz’s lesson plan here and here, we can see that this a well-crafted time and motion study; brilliant in its execution but unsettling in the wider social context.

Making a virtue of “economic necessity”

The first thing to note about pair work is that according to the economics of TEFL (i.e. its pricing mechanism) pair work is less valuable than working directly with the teacher. Almost all schools, colleges, universities etc generally charge more for smaller classes and charge most for one-to-one teaching. This is a simple fact and worth emphasising before we address the issues of “the importance of pair work” and “the need to maximises student-student interaction”.

Indeed, economically, it is the teacher who creates value (i.e. profit) in the classroom and not the furniture or other overheads. This may seem somewhat counterintuitive given that many schools seem to take more care of the furniture or computer lab rather than the teacher (3), but this is the nature of profit system. By minimising the labour element of the teaching situation (i.e. 20 students to one teacher) the school can maximise profits. Clearly there is a limit to how many students a teacher can effectively accommodate (pedagogically) so many language schools restrict classes to around 16 learners. It is still the case, however, that the teacher’s hourly rate rarely varies, whether they are teaching one-to-one classes or 30 students. Generally speaking, the first six students generate the same profit as a one-to-one class, so the extra students make an even greater profit. We say this because much that is written about pair work uses the language of student-centeredness. Student-centeredness, in such literature, is taken to mean where pair work/ group work (Student Talk Time) is encouraged and teacher input (Teacher Talk Time) is discouraged.

For us, therefore, so-called “student-centeredness” is nothing more than making a virtue out of a crude economic necessity. Liz puts it beautifully here:

When I encounter students who want to talk to me all the time in a lesson (flattering though it is) I advise them (politely) to consider having individual lessons if they want the teacher’s full attention all the time. If that doesn’t work I explain like this: 60 minutes divided by 6 students = 10 minutes each; so they can each talk to me for 10 minutes and I will listen to each of them for 10 minutes which is sad really when they’ve paid for a 60 minute lesson. And, let’s face it, it wouldn’t really be 10 minutes because you have to take time off for taking the register at the beginning of the lesson, giving everyone time to hang their coats up, sit down, get settled, receive their worksheets, read the instructions, listen to the teacher presenting grammar points or whatever, do a listening exercise or a roleplay, go through homework together, receive more homework, get ready to leave etc. 5 minutes would be more realistic. So there you have it, pay for 60 minutes and get 5. Where’s the logic?

In none of the literature, however, are we told, that, “more than six people is undesirable in a language learning context. In the interests of profit, however, it is best to adapt your teaching to ensure that the language is being learnt efficiently (or at least the impression is given that it is being done so)”

The “importance of pair work” and the need to maximise Student Talk Time merly serves as ideological cover for the mass-production model of TEFL, with its emphasis on reducing school inputs and maximising student outputs.

Education and Reform

Now, some readers may retort that much education is imparted (rather successfully) in larger groups. The difficulty with this idea, however, is that you cannot claim a special case for language learning and pair work if you claim it has no different properties than general education. Surely, the whole ethos of pair work in Foreign Language Teaching is, as Marc Hegelsen (ELT News) points out, that:

“The students need to speak English to learn English. English is not only the goal, it is also the pathway to that goal.”

Now, again, there are those readers who might believe that the models of EFL with its insistence on pair work are equally applicable to all other disciplines like maths, physics, music etc. If such subjects are taught in such a teacher centred manner rather than the superior EFL manner then much educational value is lost. Under such a view, a constructivist view of education is being used to stress the centrality of learner involvement (something we, as Marxists, obviously don’t disagree with). This, however, is to confuse an appreciation of the need to encourage peer co-operation and experimenting with hypothesis, with the “percentage requirements” concerns of modern foreign language learning.

Obviously, peers coming together to share their knowledge is essential,. We may borrow terminology from Vygotsky and argue that students of a same level occupy the same zone of proximal development (the stage just ahead of where they currently are) and each student can help the other as they are encountering almost identical issues in their language development. Arguably, the interlanguage of mono-lingual groups (the type of language produced by nonnative speakers in the process of learning a second language)might also provide better scafffolding (learning support in making the next stage easier to reach) than the teacher who doesn’t have the same grasp of their students’ interlanguage.

This, however, is a different argument from maximising Student Talk Time. It is not the quantity of the experience but the quality of the experience. For example, if a student were to explain something to another student (or, even better, whole class) in their native language far better than the non-native teacher had attempted in whatever language, then such an explanation would be more valuable than any amount of repetition in English. Moreover, discovery type exercises, like those contained within the silent way methodology, help students explore and consolidate the structure of language rather than “learn” through simple repetition and correction of discrete language items. Simply put, talking English is not always the best way to learn, listening and thinking are of equal, if not greater, importance.

But students need to talk.

Undeniably, it is through practising language that certain words/structures become somewhat more automatic and we become aware of problems or absences in our linguistic repertoires. This is not to conclude, however, that pair work is necessarily the most effective means of achieving this. One-to-one tuition, group work, presentations etc can all achieve this. However, all the alternatives are often far more resource heavy. One-to-one tuition is “very costly”, presentations are time-consuming (especially if other students are being asked to concentrate on something they have no interest in) and group work has greater maintenance issues than pair work (divisions of responsibilities etc.).

We could, however, introduce a more meaningful concept, one of maximising time in class where “all students can be heard”; where their opinions, ideas and information are encouraged and can be listened to and acted upon. The student, therefore, will not be asked to talk for the sake of talking but invited to participate. The input from the teacher, or the exercises, is designed to allow for participation (meaningful expression) rather than demand it (mechanical expression). Pair work is just, therefore, one more means of achieving this and should not be privileged over other means. We would also encourage, students to form their own preferences with respect to pair work (not ruling out the occasional change for reasons of freshness) rather than “break up” affinities formed spontaneously between human beings.

Chuck Sandy (ELT news) puts it rather nicely (editor’s emphasis in bold):

This is not to suggest in any way that teachers should dispense with activities, games, and tasks, but to point out that it’s often the less structured moments of a class which prove to be the most fruitful and that teachers should be aware of them and ready to follow such moments to where they lead. It’s also to say that a good language teacher is no different than a good teacher of any other subject, for as any good teacher does, a good language teacher creates a comfortable classroom with positive group dynamics where spontaneity is valued and everyone has a chance to be heard.

In addition, like all effective teachers, the effective language teacher uses relevant, intriguing materials as a springboard and not as a means to a particular end. Such materials allow for digressions and leave room for spontaneity and allow both teacher and students to ask real questions of value which go as far as possible beyond the simple comprehension questions most of us rely upon.

Therefore, the effective language teacher, like all effective teachers, thinks about the types of questions he or she asks and realizes that it’s not the teacher’s voice in the classroom that’s central, but the voices of students.

Indeed we at Marxist TEFL are arguing nothing other than this. Where we differ is that we situate these tendencies in their wider socio-economic context. For us methodolgy is not simply an issue of personal choice or “efficiency”, it is a political choice. We urge teachers, and especially teacher trainers, to encourage spontaneity in the classroom. To respect the choices and voices of the learner group and not to break these relationships into ever-moving constituent parts driven by the need for output. To do this we need to move beyond stale concepts of STT (Student Talk Time) and TTT (teacher Talk Time) and rid ourselves of the time and motion mentality that goes into much rigid lesson planning. We are not doing our students any favours and, despite the creation of impressively well-structured “lesson plans”, we are in fact de-skilling ourselves.

Notes.

(1) We chose Liz’s work because, unlike many EFL material writers she actually thinks about the “why” not just the “how”. If we have been critical, it is because we believe she has not gone far enough with respect to her “why” question

(2) This definition of Taylorism describes well the type of lesson planning/pair work we refer to:

It was found out that the basic form, or the “ancestor”, of learning in mass production was the new distributed system of optimizing the methods for performing repeated tasks. This type of generalizing was based on the varying ways individuals were performing the same task. In Taylor’s system, specialized planning officers analyzed this variation with the help of time-and-motion studies, and objectified the result in a new type of artefact, the work standard, which comprised the ”one best method” to perform the task. The generalized operations embedded in the standard were thus results of a process of empirical generalization.

(3) Indeed, if schools were to buy furniture like they hire teachers many would buy self-assembly packs of furniture that last only nine months and that the teachers and students would have to assemble themselves during the course.